“Write a short descriptive passage,” suggested the red-headed creative writing teacher who sat uncomfortably at the head of the table. We eight acolytes bent our heads submissively, pondered, and began to write.

That didn’t seem to be a far-fetched goal at the time. I had a good command of my adopted language. I’d spent my first year in Israel in Hatzor Haglilit, a development town up north more forgotten and forsaken than Brigadoon – when visitors chanced on that mythical Scottish town once a century, they at least found it charming and were tempted to stay. Hatzor was a centrifugal village – whoever could get out left, and those that remained did so only because they were at the bottom of the bucket. There was little to do and nowhere to do it, nothing worth seeing and nowhere to see it, and only two inhabitants who spoke English. My ulpan Hebrew was quickly supplemented by street slang and underclass argot.

Beyond that, I forced myself to read Hebrew as much as I could. I refused to buy a newspaper in English (and in any case, The Jerusalem Report didn’t exist yet). Instead, I took out a subscription to Omer, an easy Hebrew daily then published by the Histadrut’s newspaper, Davar. Each morning I spent an hour or so with the four-page tabloid and a dictionary, making myself word lists. I memorized the words as I went about my largely ineffective work as a volunteer trying to help straighten out delinquent youth in the town’s southernmost neighborhood.

By the time I moved to Jerusalem the following year and met Yuval Elizur, an editor at Maariv, I apparently seemed earnest and ambitious and fluent enough for him to assign me some small articles to write. For a few months, he even imposed on his colleagues a short weekly column by me about the tribulations and excitements of being a new immigrant. Wow, I thought to myself, look at me! Just two years in Israel and I’m writing in Hebrew!

By this time I’d begun to read Hebrew literature. I took a correspondence course on the Hebrew short story from the Open University and encountered the classic writers of the early modern Hebrew canon: Bialik, Berdichevsky, Baron, Shofman. I was in good company. For all of them, Hebrew was an adopted language.

So as I chewed my pen and scribbled down words at the long, narrow table in the long, narrow room, it seemed to me that I was in a pretty good starting position. True, the seven other aspiring writers were all native speakers, and one had published a children’s book. But I’d published more Hebrew writing than they had. And in a major daily newspaper!

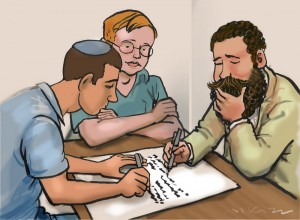

I chose my words carefully, pondered my sentence structure. It was exciting. I felt like Joseph Haim Brenner at his yeshiva in Pochep in the Ukraine, huddling with his friend Uri Nissan Gnessin, the rebellious son of the yeshiva’s headmaster, over secular Hebrew newspapers and literary magazines like Hashiloach and Ahiasaf – and laboriously putting out their own handwritten journal. If these two teenagers, who grew up speaking Yiddish, in poverty and under an oppressive regime, were able to turn into giants of modern Hebrew literature, didn’t I have a fighting chance? In fact, I had a head start on them. I spoke Hebrew at home with Ilana. A fierce advocate of Hebrew as a modern literary idiom, Brenner long believed that it could not and should not be a spoken language.

Neither had Brenner had the benefit of the total Hebrew immersion provided by the Israel Defense Forces. Clumsy, thickset Brenner had been a soldier in the Czar’s army, but that was a period of frustrating disconnection from the Hebrew literary world in which he was already a rising star. With the stubborn idealism of a young man in his mid-twenties, I supplemented the hardships of my six months of arduous basic infantry training with the vow that I would not, during this period, read in English. Not that I had much time for books, but even when I was out for a weekend I didn’t read anything fun or relaxing. I pushed myself through Amos Elon’s biography of Theodor Herzl, Menachem Begin’s Siberian memoir, and Agnon’s short stories and novellas. Boot camp ended with a 40-mile march and a big parade, followed by a few days off. The thing I remember most fondly about that short leave was not, as you might expect, being able to sleep as much as I wanted. It is the sublime delight I felt reading a novel in my native language after six months of self-imposed Hebrew asceticism. (It was John Fowles’ The Magus – in English, but with a Latin punch line.)

The red-headed writing teacher cleared his throat and we put the final touches on our written improvisations. Before he’d walked in, some of the other people around the table had mentioned that they knew him as the broadcaster of a radio interview and news show, and as the author of a book of short stories and a novel—and of another novel that was to be published in the near future.

The teacher asked the woman on his right to read her work. It described a river bank, the reflection of trees, a rowboat rising and falling on a quiet but powerful current. Then the man to her right offered his depiction of a European city square, and the woman to his right a portrait of a downtown intersection. Their language flowed, although their sentences were too long for my taste.

When my turn came I confidently declaimed my composition. I don’t remember what I wrote about, but I recall that I was the only one who put a character into his descriptive passage, and that I thought that my sentences were sharper and more precise than those I’d heard so far.

The other writers smiled politely. The unassuming teacher pointed out a couple minor grammatical errors and suggested that the passage required polish. The woman to my right read from her notebook.

I was sure that I had written well, but it was clear that no one else thought so. Were they just wrong, or could it be that I simply didn’t have sufficient grasp of my new language to tell the difference between good and bad prose?

I attended one more meeting of that class. I read a short story I’d written, which garnered much the same response. Discouraged and unsure of myself, I quit. I soon gave up my efforts to become a freelance journalist in Hebrew. The pay was just too low compared to what I could get writing for English-language publications overseas.

It also became clear that I couldn’t support a growing family just by newspaper work and that I’d need another source of income. I received a call from Tom Segev, then editor of a lively weekly magazine, Koteret Rashit, where I’d tried unsuccessfully to land a job. He’d commissioned a young Israeli writer who was fluent in Arabic to spend a few weeks traveling through the West Bank. An entire issue was to be devoted to the writer’s account of his travels. The New Yorker was already interested in the project and he needed a translation. Could I do it? The writer’s name was David Grossman – the self-effacing teacher from my writing class. I’d just read his new novel, See Under: Love, which had been an Israeli bestseller and was about to become an international sensation. The West Bank account was called The Yellow Wind and I soon found that while no one was interested in my original Hebrew work, many were glad to pay me to turn Hebrew prose into English.

Brenner was no Hebrew purist. He wrote in Yiddish when he needed the income. The difference was that he lived as a loner. When he finally married, the marriage was a failure and his wife eventually left him, taking their son back to Europe. Brenner kept writing, in Hebrew. Willingly or unwillingly, he sacrificed his life for art – and for the Hebrew language. It was a sacrifice I wasn’t going to even try to make.

I wrote in English, feeding my family and getting my kids through school. Then I had an opportunity to write a book in English. Freed from the constraints of the news article (lede, nut graf, inverted pyramid, all that), I exulted in what I could do with my mother tongue.

I wrote another book. Grossman’s agent told me: when you publish your second book, that’s when you’re allowed to call yourself a writer. So I’m a writer, as I dreamed. But like all good dreams, it’s got a rough lining: I’m a writer, but not in the language of the country I live in. Not in the language that I really wanted to write in.

I still read widely in Hebrew. Newspapers, novels, non-fiction. I’ve developed a much better grasp of Hebrew style than I had back when I read out loud my descriptive passage in that creative writing course. Enough of a sense of style to realize how little style I have in Hebrew as compared to English. It’s a fact, but not one I easily can accept. Maybe, I keep thinking, I just didn’t try hard enough.

What would Brenner say?

Links to more Necessary Stories columns

Its impossible to know what Brenner would have said. He was murdered by progressive Arabs in occupied Tel Aviv in 1921. As Professor Sternhell once said, its ok to murder settlers. Tel Aviv is a settlement on occupied Islamic Waqf. Dont take my word for it, ask any Palestinian