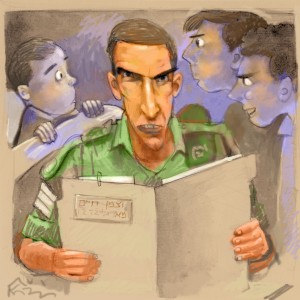

It was early summer, 1987, and I’d received a brown envelope requesting that I report to my reserve regiment’s field security office at a particular time on a particular day. I knew very well what it was about.

“No,” I said, working to keep my voice level. “I went to Jordan, too.”

The kid leaned back in his chair and the faintest of smiles played over his lips.

“We know.”

I’m suddenly back in fifth grade, when Mark Glick and Mike Sheltzer were monitoring my brain.

I am dubious. “Dubious” derives from the Latin “duo,” two. When you are dubious, you are of two minds. A man of two minds is never a good fit for an army, which is a kind of organization that extols single-mindedness. And with me, two minds is a lower limit. Usually, as the poet said, I contain multitudes. (Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself.)

“What do you know?”

“Where you were. Who you met.”

“So where? Who?”

He picks up his pen in expectation. “Why don’t you tell me?”

One of my minds is about to say to him: “Kid, this is the oldest trick in the book.” Another mind is wondering whether he’ll let me call home before casting me into a windowless dungeon.

I’m lying in bed. My brother is snoring on the other side of the room. Mark Glick lives up the street. He is even smarter than me, especially in math, and is always one of the first kids called when sides are chosen for kickball in the schoolyard. I am never chosen; I am forced on one team or another, or made permanent catcher. Mike Sheltzer is Mark’s good friend, popular, personable, and good-looking (for a ten-year old). They are in Mark’s house, sitting in front of a device of their devising which enables them to communicate with me telepathically.

“I’d really like to be your friend,” I tell them.

“We know.”

The Chronicle of Higher Education had asked me to do a story on the Jordanian university system. This was a decade before a peace treaty made communication with and travel to Jordan simple. It was still an enemy country. I could enter the kingdom from the Allenby Bridge with my U.S. passport, but to leave Israel I needed the army’s permission. I began setting up meetings on the other side. And I contacted my regiment’s field security office to obtain the necessary document. The security sergeant had me fill out some forms and promised that I’d hear from him soon.

My family had moved from Ohio to Silver Spring, Maryland, in the summer before ninth grade. Such transitions weren’t easy for me. I did not make new friends easily. Since I was bad at sports, the other males did not seek to make alliances with me at school, and I was no fun to play catch with afterwards. I earned some grudging respect for reading lots of books—my bar on Mrs. Sacks’s reading chart was longer than that of any of the other boys. But whatever Freudian magic I might have hoped for was ruined by the fact that the only other kids with such long bars were girls. Mark and Mike, best friends, were virtually the only other boys who shared any of my interests. So they were my friends, sort of. And that was all I had. But they were friends with lots of kids. And those friends were friends with lots of kids. Lots of kids were friends with lots of kids, and I was on the outside.

After about a year and a half of this, one of my minds discovered that Mark and Mike weren’t just best friends with each other. They were also best friends with me. Just that it was a secret. How did I know? Because they told me. But they couldn’t just tell me in front of anyone, because it was a secret. So they told me at night, in the dark, over the airwaves to my brain.

But in phone call after phone call, the security sergeant kept putting me off. The Jordan permit was difficult, it required this officer’s approval and that officer’s signature. Finally, a week before my mid-May trip, he told me that the permit would be ready only in June, at the earliest.

I already had appointments set up and the newspaper was eagerly awaiting my report.

I couldn’t cross the bridge. But I could easily go to Egypt, a country we were at peace with. So I bought a ticket to Cairo, and when I got to the Cairo airport I walked over to the Royal Jordanian counter and bought myself a ticket to Amman.

I concentrate toward them that are nigh. Another mind intrudes. “How do I know,” I ask Mark and Mike, “that this isn’t just my imagination?” I did not say that my imagination had cooked up much weirder things and that I was wary.

“Best friends believe,” Mark says to Mike.

“If you want to be our best friend, you have to believe,” Mike says to me.

“Anyway, doesn’t it seem real?” Mark asks.

“Yes,” I admitted.

“So isn’t that enough? Remember that this is a secret.”

I screwed up my courage.

“I’m a journalist,” I said. “My meetings were purely professional. Beyond that, I can’t say anything.”

The sergeant looked at me in surprise.

“Assuming that you are a patriotic Israeli,” he said, “I would think you would want to cooperate. Especially given your political activity.”

“My political activity?”

“Maybe you’d like to tell me about the Palestinians you get together with in the territories.”

“That’s none of the army’s business,” I protested.

“Anyway,” the sergeant said, leafing through my file, “we know all about it.”

“Then you don’t need me to tell you.”

“You need to believe me,” he replied, “when I say that nothing is going to happen to you. Just help us out a bit.” (Talk honestly, no one else hears you, and I stay only a minute longer.)

“Why does this have to be a secret?” I ask Mike and Mark.

“Why?” they asked in unanimous surprise.

“I mean, why can’t we be best friends just like everyone else?”

I can’t actually hear this, but I know that Mark is looking at Mike, and Mike at Mark.

“Well,” says Mike. “There are reasons. Important reasons.”

“There are things we can’t tell you right now,” Mark says. “But it’s connected to something big. Much bigger than just us.”

“When the time comes,” Mike says, “you’ll know.”

“We know it’s not easy,” Mark reassures me. “But your position in the class is part of the plan. It’s not easy to be alone, but it’s your contribution.”

The sergeant’s eyes narrow and his lips purse. “This is not what I anticipated,” he said, anger building in his voice. “I expected more cooperation from a man like you.”

I kept silent.

“I’ll have to pass this on to my superior officer,” he informed me. “He won’t be pleased.”

“Look guys,” I say. “I want to help out, but I need a sign.”

“A sign?” asks Mike. “What kind of sign?”

I think for a moment. “Tomorrow morning, at 10 a.m. on the dot, one of you gets up from your seat, walk over to the window closest to me. If it’s open, close it; if it’s closed, open it. Then I’ll know.”

“Can we do that?” Mike asks Mark.

“Only if it doesn’t give away the secret,” Mark says to Mike.

“You’re always opening and closing the windows,” Mike notes to Mark. “So if you do it, it wouldn’t be unusual. I don’t think anyone would suspect.”

“Okay,” Mark says. “I’ll do it. Ten a.m. tomorrow.”

“Anything else?” I asked the sergeant.

He shrugged his shoulders. “Not from me.” He took out another file and began to examine it with great interest.

“So I can go now?”

“If you want to, you can go,” he said without looking up.

The next morning the teacher got excited about Ponce de Leon and her history lesson went slightly past 10 a.m. But as soon as she was finished, at 10:07, Mark Glick got up from his desk, walked over to the window closest to me, and opened it. A warm, slightly moist breeze blew in and ruffled my shirt. Mark looked me straight in the eye, then walked slowly back to his seat.

I hesitated for a moment.

The sergeant looked up. “Unless, of course, you’d like to talk after all.”

That night, Mark and Mike contacted me again.

“So,” Mark asked, “Can we proceed?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I’m of two minds.”

Links to more Necessary Stories columns