Haim Watzman

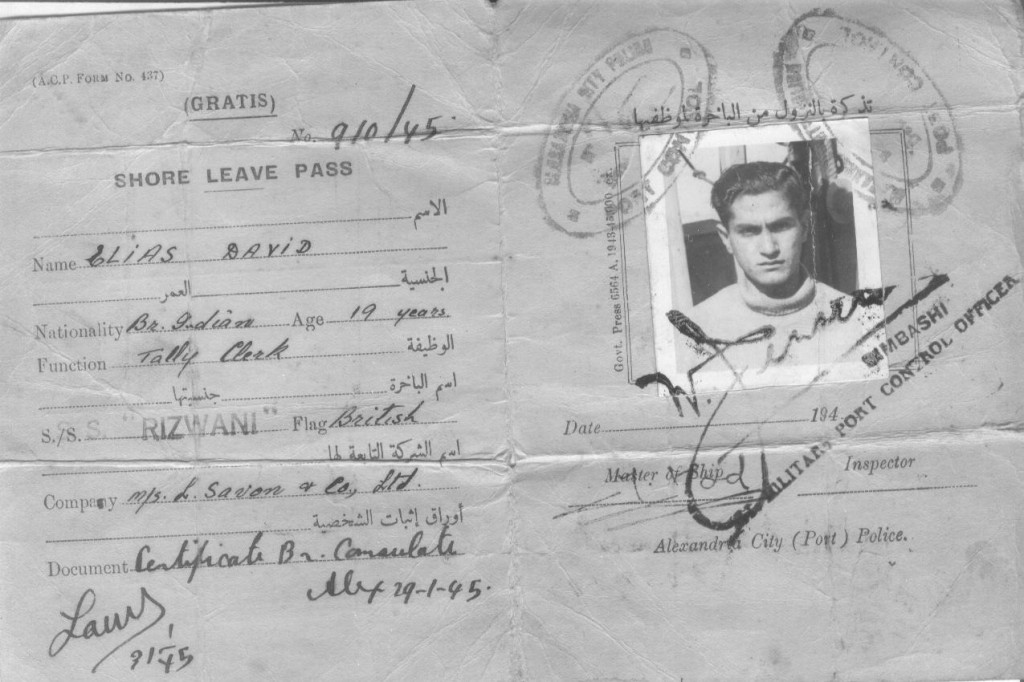

He’d been on the boat for three weeks, sailing from India’s west coast across the Arabian Sea, into the Gulf of Aden, through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal to the cosmopolitan Mediterranean port. Apparently there were no stops along the way — on his pay slip, nothing is listed under “cash advances during the voyage.” Or perhaps there were and he chose not to disembark. The Rizwani, merchant carrier of the Mogul Line, Bombay, was built in Glasgow in 1930 expressly to ferry Muslim pilgrims to Mecca. While the pilgrimage season had been the previous month, the ship might have stopped at an Arabian port, and Tally Clerk Levy might have thought it best to stay on board.

After being cooped up on what was, by merchant marine standards, a small boat, he was probably eager to get off and explore. The port he’d landed in had a reputation for offering exotic adventures and pleasures that would not get reported home. Bing Crosby was on the radio that day, singing “Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive” with the Andrews Sisters. The good-times, Father Divine-inspired prosperity gospel sermon had hit Billboard’s charts: “You’ve got to ac-cent-tchu-ate the positive/E-li-minate the negative/Latch on to the affirmative/Don’t mess with Mister In-Between.”

After being cooped up on what was, by merchant marine standards, a small boat, he was probably eager to get off and explore. The port he’d landed in had a reputation for offering exotic adventures and pleasures that would not get reported home. Bing Crosby was on the radio that day, singing “Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive” with the Andrews Sisters. The good-times, Father Divine-inspired prosperity gospel sermon had hit Billboard’s charts: “You’ve got to ac-cent-tchu-ate the positive/E-li-minate the negative/Latch on to the affirmative/Don’t mess with Mister In-Between.”

It was the last day of the Battle of the Bulge; British ships like the 5,500-ton Rizwani had been sunk right and left for the last four years. He was alive, he’d broken free of his peripatetic, always indigent parents and numerous brothers and sisters in Bombay, he was 19 and good-looking, and Crosby was singing: “You’ve got to spread joy up to the maximum/Bring gloom down to the minimum/Have faith or pandemonium/Liable to walk upon the scene.”

This wasn’t the first time he’d left his family. Three years previously, he’d lied about his age and enlisted in the British army. He wasn’t out to be a hero and definitely didn’t want to get killed. With the entrepreneurial spirit that seems to have been part of the genetic inheritance of his Baghdad forebears, he seems to have assumed that he’d be able to wrangle himself a desk job with regular hours, far enough from home to be independent but not so far as to be deprived of the pleasures of the big city.

When he got shipped far north for combat training he broke down and wrote home, and his sister Rachel made her way by rail and bus, a journey of many days, to present his birth certificate at the camp gate and demonstrate that her wayward brother was underage.

As best I can tell from the stories I heard from his widow, he was a restless youngster who wanted independence. His father’s genes for business success were profoundly disabled. Other Baghdadis were doing quite well despite the war, taking advantage of the British Empire’s broad horizons. But his father limped and sailed from one bad investment to another. During Elias’s childhood, his father had been certain he’d get rich in some El Dorado beyond the seas. He dragged his family to Shanghai, where no one wanted to buy his cloth; his store failed and they returned to Iraq. He heard that there were opportunities in Rangoon and, even though everyone warned him that it was farther from civilization than, as the irreverent Arabic expression had it, tiz al-Nabi, he insisted on going, lost what little he had, and came back.

The next move was to Bombay, where another business failed, he fell ill, and his wife and kids had to work to keep the family clothed and fed.

Maybe it wasn’t really that bad — Elias’s mother told her granddaughter years later that there, back in the old country, she didn’t need to sit on the floor with a kerosene stove and pots ranged about her to prepare Friday afternoon’s kubbe, Friday night’s meat, and Saturday morning’s chicken hamin. She’d had servants to cook and clean back in Bombay, she said. Maybe the Levys weren’t that poor, or at least not anywhere near as poor as their Indian servants. But Elias was eager to get away.

As Arab-Jewish colonials living in British India, Elias and his siblings were casually multi-lingual — the official language at home was Arabic, but school was in English and you needed Hindi for the street and market. They were traditional, very conscious of their Jewish identity but not particularly interested in it. Elias the 19-year-old sailor might have been quite ready to shake off his heritage; he was never one for rabbis and if he saw any Jews as his exemplars, it was probably the wealthy Sassoons of London and not the hardscrabble pioneers of Palestine. Maybe he thought that after a few sea voyages he could make his way to England.

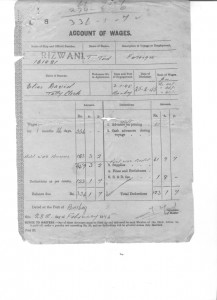

He signed on the Rizwani on January 3 for a 52-day tour. Pay was £459 3/2, £336 basic and the rest a war bonus. As tally clerk, he was responsible for inventorying cargoes coming into and leaving the ship. It was considered a good post, his widow told me, because baksheesh, while illegal, was common practice, and the tally clerk could fudge the numbers so that importers and exporters could ship more and pay for less. In later life, at least, Elias was known for his honesty and instilled in his kids the importance of having a good name. And indeed the Rizwani took him on for at least two more tours subsequently, so perhaps he resisted the temptation to exploit his position for selfish gain.

He signed on the Rizwani on January 3 for a 52-day tour. Pay was £459 3/2, £336 basic and the rest a war bonus. As tally clerk, he was responsible for inventorying cargoes coming into and leaving the ship. It was considered a good post, his widow told me, because baksheesh, while illegal, was common practice, and the tally clerk could fudge the numbers so that importers and exporters could ship more and pay for less. In later life, at least, Elias was known for his honesty and instilled in his kids the importance of having a good name. And indeed the Rizwani took him on for at least two more tours subsequently, so perhaps he resisted the temptation to exploit his position for selfish gain.

Since I never met him, I can’t quite get a handle on his personality. And if I’d known him it would have been when he was three times the age he was when he went ashore in Alexandria. So I can’t really guess what he did in the city that Lawrence Durrell said had more than five sexes. Despite his tough demeanor, maybe he was a shy kid who, whatever his ambitions, did not do much more than drink tea close to the dock and, perhaps, look up the friend of an uncle who happily put him up for the night. Maybe he let his older mates lead him to a rowdy bar and beyond, or maybe he set off resolutely on his own in search of heretofore forbidden pleasures, only to be overcome at the last moment by fear of disease and thoughts of his mother.

What I heard from his widow is this: after two years on and off the Rizwani, he returned to Bombay. He opened up a dye shop and worked around the clock to get the business going. He managed to save up a nest egg. He lent his father all his savings when the latter needed to travel to Baghdad for an eye operation, and never saw the money again. Bing had sung: “To illustrate his last remark/Jonah in the whale, Noah in the ark/

What did they do/Just when everything looked so dark?”

Someone — a friend, a relative, a Zionist emissary — suggested that he try his luck in the new state of Israel. Elias decided to accentuate the positive. He arrived here in 1950; the rest of his family followed soon after.

These were tough times; hundreds of thousands of immigrants were pouring in. There was no place to house them, food and clothing were being rationed. The Levys managed to avoid the transit camps and tent settlements where most of the immigrants languished — they found a home in Jerusalem. Elias, now Eliahu, was introduced to a young motherless girl named Esther and they married. They rented a room in the cellar of a stone house in Katamon. Children came one after the other.

Work was hard to find, so when a Persian housepainter down the street offered Eliahu a job, he jumped at it. He learned the trade, but Jerusalem in those years was a backwater. There was little construction and people didn’t have money to hire painters.

So he moved his family to Tel Aviv, and then to Holon, working for contractors and finally setting up his own house painting business. He didn’t have a car or a truck; when he had a job he’d hire a cab to get the heavy paint cans and ladders over to his workplace, then bicycle back and forth from home to work with his brushes and sandwiches. He’d hang the paint cans, turpentine, and brushes from the ladder, climb up and straddle it, and walk the ladder and his gear along the wall he was painting, like a clown on stilts.

Eliahu and Esther had four kids and lived in a tiny two-room row house in Holon’s outlying Rassco neighborhood; sand dunes, ridge after ridge of them, lay just beyond their doorstep. He worked hard and eventually they were able to move into a three-room, fourth-floor walkup in central Holon. The kids grew up. The two boys inherited their Dad’s wanderlust and, after their army service, set out to explore the world.

They both came home for a visit during Hanukka in 1978. Eliahu was working then in a public building with high ceilings. He put his ladder on a table to get up to a high spot. Perhaps he forgot for a split-second that the ladder wasn’t on the floor and tried to do the walk. The ladder tottered and Eliahu, like Finnegan, had his fall. He died on December 31, four days short of the 33rd anniversary of his engagement on the Rizwani.

I’d arrived in Israel two and a half months previously, but I wouldn’t meet his daughter, Ilana, for another six years. We had a January wedding, in Jerusalem, 40 years after Elias’s shore leave in Alexandria.

I’ll never see, or know, or really miss Elias, because I never knew him. I married a woman whose sire I never met. But this last Shabbat, when she showed me the packet of papers with the shore pass and the photo of her young father, I saw my own children’s face in his, and my own sons’ restlessness in the scraps of his story that the crumbling pay slips tell.

Crosby sang: “Gather ’round me children if you’re willin’/And sit tight while I start reviewin’/The attitude of doin’ right.”

My wife’s father, the strapping young Jew from Bombay who set out that January morning to explore Alexandria, lives on invisibly between me and my children.

*******************************************

“Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive”–Music by Harold Arlen, lyrics by Johnny Mercer

Links to more Necessary Stories columns

Strange that we will say much about socio-political process, but little about the innumerable lives which silently, mostly unknowingly, make that process. I think the cultivation of family memory can be a boon to us all. After all, that is what is lived.

Harder to hate a label when you see some of what is behind it. True of many labels, many.