Some years ago, when my family was young, I had a neighbor with very strong opinions. Strong and often different from my own. Gavriel was warm, generous, devoted to his family, humble before his God, and dedicated to his country. He died suddenly and far too young.

In the years before his death, Gavriel underwent not a spiritual awakening, for he’d grown up observant and believing, but a spiritual deepening. He spent long nights immersed in Hasidic texts and studied Talmud with a black-coated partner from the Bratislaver community. He grew sidelocks and wore longer fringes under his shirt. But he continued to serve in his IDF reserve unit long after the usual age of retirement.

At the memorial service held on the first anniversary of his death, one speaker praised Gavriel for his temimut, a Hebrew word that that, in the Bible, means “whole” and “unblemished.” In modern religious parlance it usually refers to a simple, pure piety, one that harbors no doubts. It was the right word for the occasion, for Gavriel indeed brooked none. He believed with perfect faith in God, the coming of the Messiah, in the justice of Israel’s rule over the West Bank and Gaza Strip and their Palestinian inhabitants, and in the power of his love to make his wife and children happy despite the adversities they faced. He believed these things with such fervor that, in his presence, I was often left speechless, if not convinced.

Were I myself so whole, so tamim, I would have immediately quoted to myself from Psalms 18, “I will be whole [tamim] before him, and keep myself from iniquity.” Or Deuteronomy 18, “Be whole in your faith with the Lord your God.” Or perhaps the first verse of Job: “There was a man in the land of Uz whose name was Job, and the man was whole and upright, and one who feared God and turned away from evil.”

But I didn’t. I thought instead of another poem, and not even one by a Jew. “Glory be to God for dappled things,” my heart sang at Gavriel’s memorial service, suddenly recalling the words of the Catholic mystic poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, “For skies of couple-color as a brinded cow; / For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim.”

The search for wholeness, for unity, the need to gather up the scattered parts of ourselves and our worlds is a fundamental human instinct. We all feel it at one time or another. I could not delve into the depths of Gavriel’s psyche, but it seemed to me that his yearning for unity grew in intensity as each of his four children were born. The inception of fatherhood is a watershed for every man; his world, once centered firmly on himself, grows, sometimes smoothly, sometimes awkwardly, to encompass another being when he falls in love and marries. But even then it remains a whole; what once was a circle with a single center becomes an ellipse with two foci.

With the birth of a child the figure plane is no longer sufficient. Each newly-created human being, helpless, in need of sustenance, education, and direction in life, pushes the formerly smooth and perfect shape out of whack, into unrecognizable shapes in new dimensions that send a father in search of rules, boundaries, and explanations.

As Gavriel’s family grew, the world around him, Israeli society and the religious community in which he’d grown up also transformed. Concepts and claims that had once been uncontroversial, unquestionable, and fundamental to his identity suddenly grew fluid, came up for discussion, took on new forms. Israel had once always been right, the Arabs always wrong; Judaism defined clear and separate roles for men and women; political parties had clearly-defined and distinct ideologies.

In the decade that began in the mid-1980s, unity governments, Talmud classes for girls, and the First Intifada and subsequent Oslo peace process undermined each of those certainties.

In my view, that metamorphosis was always fascinating, and for the most part positive – but then I did not grow up in Israel nor as part of the religious community. What I could view with a certain measure of detachment as welcome innovation and inevitable change was, for Gavriel, profoundly destabilizing. For him, the primary colors and clearly drawn lines of his youth were blurring and mixing into one another.

The center was not holding. There was too much ying in the yang.

The list of disunified, incongruous things that Hopkins lists in his poem “Pied Beauty” would have disconcerted and puzzled him: “Fresh-firecoal chestnut falls; finches wings / Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough / And áll trádes, their gear and tackle trim.” For him the landscape he saw before him, from his small Jerusalem living room, was disturbingly patchwork, jerrybuilt, menacingly multifarious.

How could one raise children to face such a world?

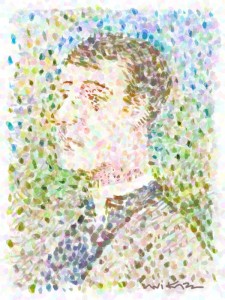

Hopkins, who came to my mind at the mention of Gavriel’s wholeness of spirit, lived a world away from the Jerusalem of that unsettling decade. An eccentric, keenly sensitive man of ascetic yearnings, estranged from his corporeality and from what he viewed as sinful sexuality, he moved, as did others of his type in his Victorian age, from High Church Anglicanism into Catholicism and the priesthood. For a time he also resisted his poetic gift, believing that it distracted him from his religious duties. He was spare, thin, short, and sickly, with the hollow, shaven cheeks of a country parson.

It would be hard to imagine a man more different than Gavriel, broad-shouldered and bearded, who performed a month and-a-half of military duty each year, on maneuvers and patrolling his country’s borders and wild places. For Hopkins a body was an impediment; for Gavriel it was a tool, and he used it well.

Yet the Catholic and the Jew had common yearnings. Both sought stability and certainty. Hopkins believed, or hoped, that God and the Church could give him that; for Gavriel it was a tripartite weave of God, country, and personal responsibility to his family.

I have a contradictory trait – I often seek out the advice of friends, but hate it when they tell me what to do. Once I consulted with Gavriel about a certain problem my family was facing. I outlined three or four courses of action and said I was unsure which was the best—each had its advantages and disadvantages. Gavriel listened carefully, offered his sympathies—and said that only one of my options was at all conceivable. Any of the others would be improper, even irresponsible, he maintained. I was taken aback by the vehemence of his response and, frankly, hurt by his conviction that a question I found ambiguous in fact had an unequivocal answer. So I did not do as he advised—and the problem found a solution, more or less.

For all the vast differences between their faiths, practices, and views of the world, Catholics and Jews share a commitment to practice; abstract philosophical and theological speculation impacts directly on what you need to do for God and for your religious community. Hopkins joined the Jesuits, and again, while the celibate follower of St. Ignatius, with his vow of utter obedience to the pope, is a world away from the talmid hacham, the Torah scholar, both are trained to plumb all sides of a question, to make out fine distinctions where others see nothing to argue about. Perhaps it was the right place for a poet who, while desperately seeking wholeness, kept noticing how disparate is the world created by the one God. He could not keep from putting it into words.

The texts that Gavriel immersed himself in—Talmud, and Hassidic tales and commentaries—are intricate and difficult. None of them can be said to have a single meaning, or even a plain meaning, a message you can take home with you, one that will tell you how to balance the family budget or get a child to do his homework. But Gavriel, like so many others, seemed to think that if he perused these books with sufficient intent, he would find just such guidance.

Hopkins’s second and final verse reads thus:

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

There is great and Godly wisdom here, a discovery, or acknowledgment, or a reading of the world. That unity of the soul that the man in search of God seeks can, paradoxically, only be found in the multiplicity, ambiguity, and weirdness of the world that God created.

I have taken a long time to write this, many years, because we are meant to speak well of the dead, and because criticizing another man’s relationship with God is tantamount to saying that one knows better than he what God wants.

But I happened to hear “Pied Beauty” read out loud last week, and it was almost like prophecy, a message that I was required to convey. But please note: what I question here is not Gavriel’s faith, which I cannot fathom and which was certainly more profound than my own. What I suggest is that eulogizing a man by saying that he was tamim, whole in his faith, may be inappropriate praise.

God was unfair to Gavriel—He took him at a young age. Perhaps, had he had a chance to gain the wisdom that years bring, had he had a chance to watch his children grow and discover the world for themselves, to see how different each one would become from him and each other, while yet preserving so much of what he gave them, his faith would have become—not less intense, not less fervent—but less of one piece and therefore more all-encompassing. Perhaps, had he died when he should have and not when he did, I would have stood up a year later at his memorial service and said: “Glory be to God for dappled things.”

Links to more Necessary Stories columns

One of your best pieces, to me.

very nice…