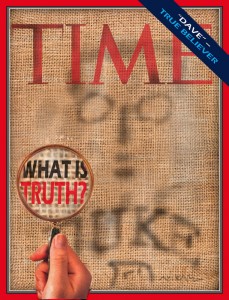

I think it was my senior year in high school in which my friend Dave first discovered the truth. And since I was his best friend, he was determined to impart the truth to me as well.

It was a cover story in Time magazine, I’m pretty sure, that set Dave off. It was a big spread about the Shroud of Turin, a cloth that many Christians believe bears an image of the crucified Jesus. New research, the magazine reported, proved that the cloth and the image indeed dated from the first century AD.

illustration by Avi Katz

“Wow,” said Dave, putting down the magazine and digging into the chocolate ice cream I’d dished out to him in my family’s kitchen. “We all gotta become Christians now!”

“Ha,” I said. Dave had, after all, been in my Hebrew school car pool. His Mom made a mean kugel and his older sister was going out with the son of the military attaché at the Israeli embassy.

“I’m serious,” said Dave. “It says here that it’s Jesus on the shroud. That means you have to believe in him.”

I grabbed his arm because I was afraid he was about to mark an ice cream cross on his chest. “I don’t know, Dave,” I said. “How can you be so sure? And let’s say they’re right. How do you get from that to the catechism?”

“What’s a catechism?” Dave asked, wrestling his arm free and stuffing more Ben & Jerry’s into his maw.

He found out. For four months he wouldn’t let me alone. He told me how he’d been born again and how he was going to heaven and that only the grace of Jesus could save me. Look, he was my friend, so I listened patiently and tried to calm my Mom down and explain that Dave was just going through a phase.

Since Dave and I were best buddies we went off to college together. College changes guys, and after a week I noticed that Dave had stopped kneeling down by his bed each night to say his prayers. He stopped shaving and his hair started growing out.

“The assassination of Salvador Allende by the nefarious forces of world capitalist oppression,” he told me, “proves that Mao was right. The march of history moves only in one direction. The peasants and downtrodden will stride on to ultimate victory and all those who oppose them—indeed, all those who do not join them—will be consigned to the trash bin of history. It is time for you to follow me into the Workers World Party.”

“We’re in college,” I said. “The parties that interest me are ones with girls.”

But it was no good. I was his best friend and he did not want to enter the socialist paradise without me. He plied me with pamphlets and dragged me to demonstrations. It seemed like we couldn’t have a conversation in which Trotsky was not mentioned. It got annoying at times, but what are friends for if not to serve as sounding boards for what you have on your mind? I tried to be a good listener.

“Why can’t you accept the truth?” he would sometimes shout in frustration.

“Well, you know,” I said. “I tend to be skeptical. To see the other side of every question.”

Ultimately, though, Russians with beards couldn’t compete with Katrina, a slender Danish exchange student whom Dave found one afternoon on the quad, standing behind the booklet-laden table next to his. Dave tried to cure her of false consciousness, but the end result was that he switched tables, from Workers World to EST.

“It’ll change your life,” he insisted, with his face very close to mine, at the EST guest seminar he organized in our room. “It’ll transform your ability to experience living so that the situations you’ve been trying to change or put up with clear up just in the process of life itself!”

He was holding a pen and a form that asked for four hundred bucks in exchange for spending an entire day locked in a hotel conference room with a guy yelling at me.

“I kind of like my life as it is,” I demurred. “Anyway, I don’ t have the money. I guess I’ll just have to wait around for the thing I’m putting up with to clear up in the process of life itself.”

“I am so disappointed in you,” Dave said. “Four hundred dollars is nothing when you get the truth in return.”

On the day we graduated Katrina jilted Dave and ran off with a Scientology practitioner. Dave’s parents, who were desperate to get their truth-hungry son on track, offered the two of us a free trip to Israel. So we stuffed a few pairs of jeans into our backpacks and set off for a kibbutz in the desert.

“At worst, the goyim want to kill us,” said Avner, the curly-haired reserve paratrooper major who went out with us to set up sprinklers in the cotton fields. “At best, they won’t lift a finger to help us. Israel is the only hope for Jewish survival. And if we die here, at least we die with honor, after fighting with everything we’ve got.”

Back on our cots, Dave turned to me and said, “You know, what Avner said is really true.”

“Uh-oh,” I said.

“We’ve got to make aliya. It’s our responsibility to the Jewish people. And serve in the IDF, in the toughest and most dangerous unit we can get into. Are you with me?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I’ve just been here one day.”

“A single day is sufficient to learn the truth,” Dave said in his wisest tone of voice.

I really wanted to go home at the end of that summer, but Dave wouldn’t hear of it. So I went with him to the Ministry of Absorption and signed up to be Israeli. His motivation: Zionism. Mine: to get Dave to shut up.

Once he became Israeli, David realized that Zionist truth came in several flavors. He started out as a committed Labor Zionist, then a devout advocate of Greater Israel. Then he decided that the true Zionist message was one of unity and he became a radical proponent of a series of movements whose truth lay in their commitment to the premise that all other Zionist truths really meant the same thing—Dash, Shinui, the Third Way and then the Center party.

Whatever it was, he wouldn’t let me alone. Whatever party he was in was the only one that could save Israel and the Jewish people. He spared no effort to force me to agree with him. Look, he was my friend, so I listened as politely as I could

It was when he was canvassing votes at the Western Wall one Friday afternoon that he was picked up by Meir, the eternal Jew who has for the last two millennia set up Shabbat meals at the Kotel. Meir’s sharp eye immediately saw that Dave was a truth seeker, a promising receptacle for the Holy Fire.

On Sunday, Dave enrolled in Aish HaTorah.

“All God’s truth is in these books,” Dave said when I visited him at the yeshiva in the Old City. “There’s no need for any others.”

“Hey Dave, it’s not for me,” I said.

“Stop resisting,” he said. “Conquer your evil impulse. You always are so full of questions. Torah is the answer.”

“I can’t help being skeptical,” I said.

“I feel so sorry for you,” he said. “The truth lies within reach and you turn your back.”

Not that turning my back helped. Dave barraged me with invitations to classes and lectures. He signed me up for newsletters and had unctuous rabbis telephone me late at night.

After all these years, it started to get to me.

“Dave,” I said to him one Friday afternoon when he was trying to drag me to his house for a Shabbat dinner. “Could you, well, maybe give me a break?”

He dropped my arm in astonishment.

“Give you a break?” he said. “But you’re my friend! How can I leave you in the dark when I’ve seen the light?”

“Doesn’t friendship mean accepting me as I am and not trying to change me into something else?” I asked.

“How ungrateful!” he exclaimed. “Don’t you understand what I have tried to do for you? My entire life has been devoted to saving you from eternal damnation, from suffering the fate of an egg broken to make the omelet of the proletarian revolution, from the angst of postindustrial existential crisis, from assimilation and a second Holocaust, from the perils of extremism, and from a life cut off from God. And you claim that I’m insensitive? If that’s how you feel, go off and live your benighted life as you wish. Just don’t come running to me when you miss the bus to ultimate redemption!”

Dave and I weren’t friends any more. I was sad about that, but it was a relief to be able to find my own way through life without someone nagging me the whole way.

Still, when my Android rang last week, it was so great to hear Dave’s voice.

“Hey,” he said. “I owe you an apology. Now I realize that you were right all along. Truth is elusive. Texts are indeterminate. Values are relative. We can only grope our way through the universe.”

“Oh Dave,” I said. “What is it now?”

“Don’t you understand? Postmodernism is the answer.”

“Are you sure?”

“I am absolutely certain,” he said. “And you must be, too.”

Links to more Necessary Stories columns

2 thoughts on “The Truth About Dave — “Necessary Stories” column from <em>The Jerusalem Report</em>”

Comments are closed.