Haim Watzman

It was Timothy Asfal’s fingers that caught my eye when I boarded an overloaded 21 bus at Davidka Square on the way home to Talpiot. I could see them clearly because he was seated in the front row, on the aisle just behind the driver, clutching a plastic DVD box. Tim has the slender, agile digits of the artistic weaver he is, so finely-shaped that you want them to touch you.

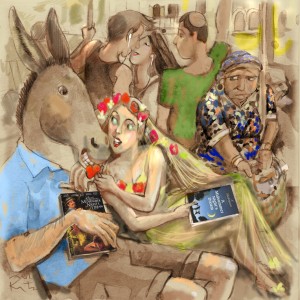

illustration by Avi Katz

Tim and I have been friends since the 1980s, when we were both lonely and dreamy young men new in Jerusalem. I valued his company then because he had the wit of a sad clown and could see deep into my soul. Even then the beauty of his fingers stood out, but I barely noticed the way he looked then, or that the rest of his body was out of proportion. Now that he lives in Beit HaKerem we don’t see each other that often, even for a year at a time. And I admit that these days, when I run into him, I am taken aback for a moment. I notice all the things that friendship once led me to disregard. His body is thick, fleshy, and hirsute. His head is long and angular, with a protruding nose and ears that are two sizes too large. Maybe, in part, these physical flaws are even more noticeable now because when he was young he had hope. He could be ironic about love because he believed deep down that despite everything he would find it. Now, in middle age, he is unhappy and lonely.

It was late on a Thursday afternoon in mid-June and the bus was packed back to front with shoppers from the Machaneh Yehuda shuk, the open-air produce market. Their baskets sprouted basil and leeks and the fragrance of raw carrots filled the air. I pushed myself onto the bus and, while I couldn’t get far, I managed to wedge myself right up against Tim’s seat, standing between a teenage couple grooving to their Ipods and each other and a Kurdish grandmother who sighed intermittently as if the entire world’s sorrows were on her shoulders.

Tim barely smiled when he saw me. His head swung back and forth slowly, first to me, then toward the fair-haired woman in a blue summer dress who sat on the seat to his left, deeply absorbed in a paperback. His head halted just where he could see her out of the corner of his eye.

“Tim,” I said. “You look as if you have just woken up from a bad dream. Where are you going?”

“To an audition,” he said listlessly. Like some other sad and lonely men I know, Tim has taken refuge on the stage. He performs frequently in the productions of Jerusalem’s several amateur English-language theater groups. And he does a good job—his Dick Deadeye in the most recent Encore production of H.M.S. Pinafore was on the mark, and he was hilarious as Pistol in a production of Henry V a few years back.

He took a sidelong look at the woman and then motioned for me to bend down toward him.

“You’ll never believe what just happened,” he whispered.

“Try me,” I suggested.

“When the bus turned on to Agrippas Street and headed into the shuk,” Tim said, “I was sitting here humming to myself—you know how I do that—and she grabbed my hand. I thought she’d seen a suicide bomber or something. I glanced at her, expecting a terrified face, but what I saw was a gaze of adoration.”

“Of what?” I said.

“Adoration,” Tim repeated. “And she said ‘Could you hum a little louder please? You have such a beautiful voice!’”

I looked at the woman, who did not seem even to have noticed Tim’s existence. The Kurdish grandmother sighed. I raised an eyebrow.

“No, really,” Tim insisted. “And then she said I was the best looking man she’d ever seen. And then she said she had fallen in love with me at first sight.”

I straightened up and gave him a long, hard look, considering how to handle this. Despite the unfortunate shape of his mortal body, Tim is a man of subtle discernment and high sentiment. He has not had an easy life and I did not want to hurt him.

“Tim,” I said slowly, “Do you think—well, I mean, it doesn’t really make much sense, does it?”

“Sense and love seldom keep company,” he objected.

I took a deep breath.

“Okay,” I said. “Then what happened?”

He reached up, grabbed my shoulder, and pulled me down to him again.

“The bus got stuck in traffic. You know how it is on Agrippas. Shoppers were running across the street, trucks were honking their horns, there were shouts from the shuk of ‘Cabbage three shekels!’ and ‘The sweetest melons in town!’ But here in the bus, as I looked in her eyes, it was like we were stranded in an enchanted forest.”

I was speechless. The Kurdish grandmother sighed once more.

“Then she kissed me,” he whispered. “Such a kiss! I haven’t ever been kissed like that. And she invited me to come to her bower.”

“Her what?” I said, jerking up involuntarily and speaking loud enough for the woman to hear. She looked up and then quickly returned to her book.

“Her bower,” Tim said. “That was the word she used.”

“Listen, Tim,” I said, bending down again and whisper into his ear. “I’ve been around a lot and I’ve never been invited to a bower. Not by either sex.”

“What are you trying to say?” he glared.

“I just mean—well, Tim, you’re a great guy and nothing would make me happier than for a woman to fall head over heels for you. But, I mean, well, are you sure you’re not dehydrated or something?”

Tim looked like he was on the verge of tears. I felt so sorry for him.

“Did she say where her bower is?”

“No,” he said, “but she caressed me.”

“Here on the bus? In front of everyone?” I said.

“Well, lots of people do,” he said. He looked up and indicated the teenage couple with the Ipods, who were by this point doing their best give the bus a rating of parental guidance suggested.

“Yes,” I hissed into his ear, “but they are 17 and you are 48 and this fairy princess of yours, while she looks incredibly good for her age, is not much younger.”

The Kurdish grandmother sighed.

“Well, thank God you don’t have to stop pitying me,” he said sarcastically. “Because it didn’t last long.”

“I’m so sorry,” I said.

“Soon the bus started moving. She kissed me again, long, and slow, and then fell asleep in my arms,” he said dreamily. “Maybe I drowsed off, too.”

“That sounds good.”

“Then the bus took the left turn from Agrippas, past the Clal building.” He looked glumly at the Kurdish grandmother, who sighed long and deeply. “And she woke up.”

I waited.

“And she looked out the window, and said to no one in particular, ‘What visions have I seen! Methought I was enamored of an ass!’”

“‘Methought?’” I said. “‘Enamoured?’ Tim, really.”

“Then she looked at me and let out a little scream,” he said. “And she quickly opened her book again and stuck her nose in it, just like you see it now.”

Poor Tim. I couldn’t bear to see him rejected again, even if he’d been rejected while hallucinating. I thought maybe it was time to change the subject.

“Say,” I said. “What’s that movie you have?”

He let the plastic case fall onto his lap.

“A Midsummer Night’s Dream?” I said in surprise. And I was suddenly suspicious.

“Why do you sound so surprised?” he said. “I’m auditioning, I told you.”

Then I noticed something that was just a little too neat.

“Hey,” I said, “That that’s what she’s reading. Maybe she’s auditioning, too?”

She looked up, and over at the DVD box that Tim was holding. Tim was staring at the box himself. I saw tears in his eyes. The Kurdish grandmother sighed and moved to pick up her basket. The teenage lovers on my other side joined hands, preparing their descent.

“Tim,” I said gently.

He kept his eyes on the box.

“It’s my stop,” I said. “I have to get off.”

“Fine,” he said, not turning to look at me. “Nice seeing you.”

“Good luck with the audition.”

“Right,” he said.

Tim looked up slowly at the woman, then followed her gaze. She was no longer looking at the DVD box. No, she was gazing intently at his fingers, the perfectly-formed fingers of Timothy Asfal.

The teenage lover relieved the grandmother of her basket. His girlfriend took the old woman’s arm and helped her down the step to the curb. I followed.

As the bus pulled away I waved to Tim. I don’t know if he saw. They were laughing.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

More Necessary Stories

Beautifully told story!