illustration by Avi Katz

Yes, that’s my seat, but don’t worry about it, just let me squeeze past, I’ve gained some weight and the belly doesn’t squeeze like it used to, I’ll sit over there next to you. No, really, it’s just fine, yes, that’s my name on the seat, but how could you know, you’re a stranger, and who would bother to tell you because I hardly ever show up. Anyway, I built this synagogue, with some help from my brothers and sisters, so all the seats are really mine. Do I smell bananas or is it just my imagination?

That young rabbi gets on my nerves. See the way he parades behind the Sefer Torah, looks just like Eli Yishai from Shas, I think at the yeshivot they bring in plastic surgeons and acting coaches to make them all look that way. Same short-trimmed beard, same beanpole physique, same clothes, same words coming out of their mouths. You think it’s not polite for me to talk to you while everyone’s blowing kisses at the holy scroll? Don’t let it bother you, like I said, I built this place and I can do whatever I want.

You know why I’m here? To say kaddish for my father. Died 27 years ago today. And not a day too soon, believe me. He was a domineering bastard. You know the kind, from the old generation, no education, no knowledge of the world, no interests beyond telling his wife and kids what to do every day of their lives and every minute of their days. Each year I tell myself that, enough, I won’t go this year, but each year I wake up on Saturday morning in a sweat. He’s been dead for nearly three decades but somewhere in my soul there’s something that’s sure that he’ll give me a whack if I don’t get out of bed and drive all the way from Shoham to the Divrei Emet synagogue in Holon.

See that silver yad that the rabbi’s holding up to point out the beginning of the Torah portion? I donated that to the synagogue when my oldest daughter went to first grade. Pretty much everything here was paid for by my family. Those gaudy flickering orange memorial lamps that light up in sequence so that it looks like the Olympic torch being carried a sprinter running up the Leaning Tower of Pisa? My brother-in-law donated those so that the souls of his uncle and aunt, killed in a horrible car accident five years ago, will go straight to heaven, as noted in large letters on each. And that impressive chandelier hanging from the ceiling over the bima, made of maybe ten thousand pieces of tear-shaped cut glass? Me and my brothers bought that for the synagogue in memory of our mother, a saint who had a very hard life, plagued by illness and fatigue, as inscribed on that large plaque hanging down in the center.

Where are you from? Jerusalem? Here visiting family? Where? Through that parking lot and up the stairs? I don’t know them. Well, what do you expect, the neighborhood’s changed since I was a kid here. This whole area was a refugee camp, hundreds and hundreds of families from Morocco, Tunisia, and Iraq.

Okay, I’ll whisper. The people have to hear the rabbi’s sermon. He says the same thing every time I’m here. I’d rather be at the beach. What’s the Torah portion this week? Balak? Yeah, it’s always Balak.

We built the synagogue on the site of Abba’s vegetable stand. See, street here, it wasn’t paved back in the fifties. When the refugees got off the planes or boats they were bused here and left to make it on their own. Each family grabbed whatever empty space they could find. See that row of houses over there? That’s where we lived.

I remember the story, I don’t need to be told like a nursery school child. Balak, the king of Moab. Scared stiff of the Children of Israel swarming in the plain below his mountain kingdom. Calls in a famous sorcerer, Bil’am, from a distant land to curse them. Offers him a lot of money. Bil’am doesn’t want to, but it’s a lot of money. He’s got a family, owes money to the magic store. So he goes.

We left Baghdad in ’51. No, I didn’t come with them. I was the oldest, I was already almost sixteen. I was in the French high school, star student, and my math teacher, a Jesuit from Marseilles, used some connections and arranged a ticket for me to Milan. He said that I could finish high school there and that if I served in the Italian army I could then get a university scholarship. So they all came here and I went to Italy. Served in the signal corps and then did a civil engineering degree. I had a job offer, could have stayed there and by now I’d be retired in a villa in Tuscany, but no, Abba insisted that I had to come home. He needed me in the store. I’m an engineer, I wrote to him. First you sell cucumbers and get your brothers and sisters through school, then you can go be an engineer, he wrote. I don’t know why I did it, but I bought a ticket and came.

And I get off the bus, right over there, see through that window, there behind us, in my white suit, carrying my fine leather suitcase, and step straight into a puddle brown with mud and donkey turds. The stench wallops me, latrine mixed with rotten tomatoes and unwashed human skin. And what do I see, a jumble of tens, shacks, lean-tos, and I hear mothers screaming in exhaustion and children weeping and clementines, clementines, get your clementines, 20 grush. And there’s my Abba waiting for me, barely comes up to my shoulder, wearing a cast-off suit jacket with holes in the elbows and a pair of pants held up with a length of rope, and he puts his hand roughly on my arm and says “Ovad, look, here’s our house and here’s our store.” And I look and what he says is a house is a box, literally a box, about the size of this room, this is where my mother and father and four brothers and three sisters are living, and I stare and I say, “Abba, where am I going to live,” and he says, “Don’t worry, I thought it out, see those boards, we’ll put them up on this side of the house and you’ll have your own room.” And he grabs me and pulls me down the street and through a field and we get here and points to four iron poles hammered into the ground with blankets hung between them and crates on top of crates of oranges and apples inside and he says, this is the store. And he starts shouting “Clementines, clementines, 20 grush!” And I say Abba, I’m a civil engineer. And he puts his hand up and pinches my cheeks and brings my head down to his and says “Now you sell clementines.”

So I sold clementines and in a month I looked like all the rest. Nearly forgot I’d ever been in Italy, ever gone to college.

I’ll give Abba something, he never had a sick day in his life, not until the end. He wasn’t a strong guy but if he had a fever or felt weak he’d just keep going, not even mention it, I’d just see him slow down a bit.

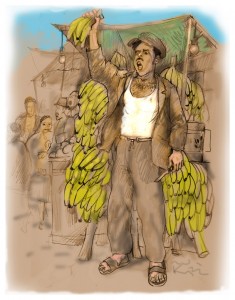

The last day? It was a steaming summer morning like this one. I’d left the store to take Albert and Herzl, my two youngest brothers, to the place where they got picked up for camp. Then I came back to the store and what do I see? The entire store is filled with huge stalks of yellow bananas with brown blotches, and outside the store on the street more and more stalks of bananas are piled up, you know, the thick stalks they cut right from the tree, with rows and rows of banana bunches on each one. There must have been a ton, maybe two tons of bananas, and they were giving off that sickly-sweet odor that means that they are perfectly ripe. Which meant that on a hot summer day within two hours they’d be brown mush. I stopped in my tracks and stared. And what’s Abba doing, he’s crouched on the ground roasting an eggplant on a kerosene stove. He sees me staring at the bananas and he says, the jobber from Tenuva asked me to do a favor and take them off his hands. And I said, Abba, how are we going to sell so many bananas before they go rotten? And he said, “You’ll figure it out,” and I said, “I’ll figure it out?” And he said, “I’m not feeling so well. When I was a kid and I felt this way my grandmother would roast an eggplant and feed it to me.” And he took the eggplant, charred and steaming, off the fire, blew on it, shook it, and then began to eat it, very slowly, peel and all. In the meantime I hear all the hawkers on the street shouting “Bananas! Ripe bananas 65 grush!” And I look and I see each stall has one or two stalks of bananas. And we’ve got two tons.

And then Abba gets up and says, “I’m going home to rest for an hour or two.”

I’m cursing him in my heart, telling myself to go back to the bus stop, get on the bus, and look for a real job in Tel Aviv. And then I look at the bananas and I don’t know what to do. I stare and stare and then I start dragging the stalks right into the middle of the street so that no one can get by and I put up a sign that says “Bananas 60 grush.” The other hawkers start screaming at me for undercutting the price and I scream back and they lower their price and I lower mine and before I know it the bananas are gone and the ten-kilo olive can that Abba kept his change in was filled to the top.

Abba hasn’t come back yet so I tell my brother Tzion to watch the shop and I go home. Abba’s sitting on the porch with the morning newspaper in his lap, staring out into space. I went up to him and said “Abba!” He keeps staring out into space. “Abba, I sold the bananas,” I say. He doesn’t say a word. I bang the can down on the floor and coins go flying and I say, “Here’s the money. That’s it, I’ve had enough, I’m leaving.” No response. I pinch his cheeks with my fingers and force his head up so he’s looking into my eyes and say “Abba, I sold the bananas. And then I see there’s no life in his eyes. He’s dead. Twenty-seven years ago today.”

Yeah, yeah, Bil’am tried three times to curse the Children of Israel, but each time the Holy One Blessed Be He put blessings in his mouth. Who doesn’t know that story?

And I got my brothers and sisters together and we put up money and built this synagogue here, right on the spot where his stall stood. And I come here once a year to say kaddish in his memory. And you know what? All year I curse him, but on this one day a year I miss him like hell.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Beautifully done. Real , vivid and bittersweet. I love Watzman’s stories, I subscribe to The Jerusalem Report, but also read at least one in an Israeli paper. I hope one day they can be published as a book. Some of them are hilarious, and all of them ring true.

My husband is no bastard, God forbid, but I sent it to my sons nonetheless.

I wonder how and where Watzman gets his ideas for his stories. They are so variegated. To me he is today’s Ephraim Kishon, but…. how can i put it? Even better.