Haim Watzman

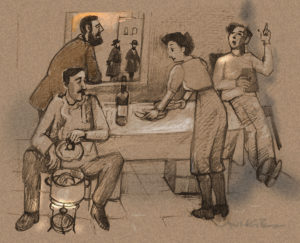

“It is a heavenly chicken,” he pronounced. “There is no pleasure on this earth greater than inhaling the scent of a cooking chicken.”

“How about an orgasm?” suggested Yanai, tipped back against a corner with his legs stretched out, dressed in a white shirt and paint-splattered work pants. The corner went dim as the final ray of the setting sun abandoned the window of Devorah Hannah’s room in Jerusalem’s Fruits of Labor neighborhood. Behind the aroma of the cooking chicken was a dank scent of mildew, brought on an hour before by a cloudburst that had come two weeks too early on that Yom Kippur eve of 1911.

“All great orgasms are, ultimately, alike,” Zealot considered, preening his moustache, “but each excellent repast is excellent in its own way.”

“Zealot has never had either,” Devorah Hannah informed Eliezer, as she set her table for four. The table was the board that served as her bed, with an additional crate added to each leg, with a white cotton sheet serving as a tablecloth. A bottle of Rishon Letzion was already open and waiting. Eliezer gazed out the window at men in black frock coats and black hats striding toward synagogues. He wore the brown gabardine suit that he generally put on only for his meetings with Ottoman officials or Baron Rothschild’s men.

“I can’t read any more,” Yanai sighed, putting down his copy of Brenner’s new novel, On This Side and That.

“Too dark?” Eliezer asked.

“The darkness of the soul,” Yanai said, slowly rising, then pushing the rickety chair toward the table. He stretched his lanky frame and yawned. “When do we eat?”

Haim Watzman

Haim Watzman

Paper Rule — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

As I rant, her face is forbearing but firm. She holds her pile of folded laundry perfectly steady. My tirade is just a fraction of the pre-Shabbat uproar of tantrums, whistling kettle, beeping microwave, high-volume radio, chair-dragging, clinking plates and silverware that fill my big sister’s small apartment. I take a deep breath in the middle of a loud sentence.

Itay, Steph’s five-year-old (number four of six) walks out of the boys’ room and stares at me. I put my hand on the lintel of the bathroom door ‒ to steady my spirit more than to hold up my body. Maybe I should leave before the rules kick in. But where would I go? Back home to Mom would be worse. Back on the road?

“I’m sorry,” I say. “Of course. It’s your place. I get it. It’s a rule.”

Steph smiles, hugs me, then holds me by the shoulders and looks at me like she used to when I’d come home from school with holes in my jeans that Mom hadn’t yet seen.

“Little sis. I love you.”

Itay reaches up between us to see who will respond first. I pick him up and give him a squeeze.

“Can I just have on record that I think, that of all the Shabbat rules you’ve so carefully laid out and explained over the last hour, this is the most ridiculous?”

The Shirt Off His Back — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

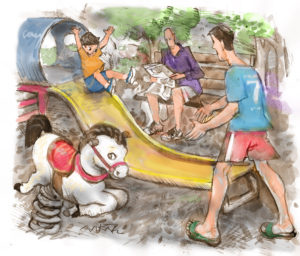

Itzik feels a little hand tugging at his but keeps his eye on the shirt. The hand belongs to Lior, his three-year-old. The shirt belongs to him, to Itzik, but Itzik is not wearing it. A stranger is.

The shirt is purple, long-sleeved, one that Itzik would never have worn on such a hot summer morning. The stranger wearing it has a sculpted, lean face and sits poised, erect but relaxed. Other than the shirt, he has on khaki cargo shorts and New Balances.

“Abba, watch,” Lior pleads, tugging again at Itzik’s hand. Itzik looks down into his son’s bright eyes, which seem to take up most of his face.

“I’m watching, I’m watching!” Lior smiles broadly, but when he sits down on the edge of the slide, his face clouds.

“Go on!”

Lior shakes his head slowly, turning it a full ninety degrees each way.

“Ok, I’ll go catch you.” Itzik clambers down the ladder and goes to the bottom of the S-shaped slide, a tunnel at its top half. Lior lets loose with a child’s primal cry and a few seconds later lands on his bottom on the rubber below. Lior screams, more insulted than hurt. Itzik looks away from the stranger, heaves his son up into a big hug. The stranger looks up at them.

Not a Third Time — Dvar Torah in Memory of My Dad

The dawn of sovereignty and the end of sovereignty, divine providence and divine concealment, standing on the verge of the Land of Israel and gong into exile—the first chapters of the book of Deuteronomy, which we read this week in the annual cycle of Torah readings, seem to mirror and contrast the themes of the fast of the Ninth of Av, which always falls in the week after it is read. The cycle is deliberately arranged so that we always begin our reading of Deuteronomy on Shabbat Hazon, the Shabbat before Tisha B’Av, the fast that mourns the destruction of the First and Second Temples and the beginnings of the Babylonian and Roman exiles. The most commonly cited connection between the fast and the Torah reading is that the word “eichah,” the exclamation that means “how can this be endured!” (The word also appears in the week’s haftarah from Isaiah and is a refrain in the Scroll of Lamentations read on Tisha B’Av.) But there is much more. The clear message conveyed by the days between Shabbat Hazon and Tisha B’Av is that the Jewish nation was given a chance to establish an independent and moral society, one acting in the name of heaven and not for its own aggrandizement—and that we failed the test badly.

My father worked for many years as a journalist out of a sense of mission and a firm belief that a free press is one of the cornerstones of democratic society. And he believed that democracy was the best (if far from perfect) way of establishing and maintaining a moral human society. Democracy requires citizens to take responsibility for themselves. On the face of it, that seems to be the opposite of what the Torah demands.

Waves — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

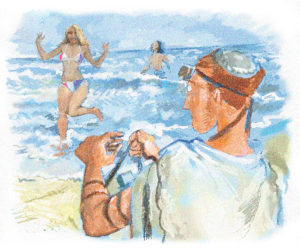

I’m just finishing winding up the straps of my tefilin when she reaches me. She stops a couple meters away and smiles, waiting patiently as I fold up my tallit and stow my prayer gear in my backpack. Then we both sit down on the mat that Barak brought back from Thailand, along with Emma. I adjust myself to put just one more centimeter between us. We do not speak at first.

“It’s a beautiful beach,” she says in English, with a heavy French accent.

I nod and take a breath to get my own Hebrew-accented English in order. “It’s our favorite. Part of a nature reserve. We used to come here a lot together. On Fridays during high school. When we were home from the army.”

“You don’t want to go into the water?”

“Soon.”

After another pause, she says: “You do this every morning? Pray? Even at the beach?”

I shrug. “Just part of waking up for me.”

“Barak used to do this, too, when you came here, before his trip?”

I nod.

“Funny,” she says. Her smile is warm, accepting, but uncomprehending. “When I wake up at the sea in the summer, the first thing I want is to go in the water.”

Somehow she’s closed up that extra centimeter.

One Flesh — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

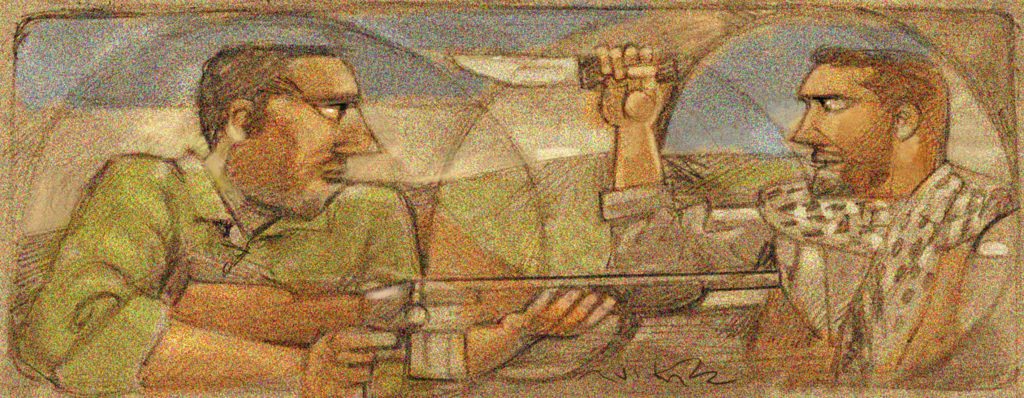

We circle, weapons drawn, two as one, ready to kill.

I raped the boy in April 1948, in a dark corner in the garden of a villa in Talbieh. A few minutes before he had leapt out from between some bushes, a butcher’s knife flashing. Boaz, a pace away from me, had his eye on the balcony above, fearing a sniper, so he never saw the kid who brought the knife down between his shoulder blades, with a shout of Allah akbar!, or perhaps it was something else. The stars were just coming out, but I saw my friend murdered. I saw the blood spurt from his back and chest as he crumpled.

To this day I wonder how, in the heat of battle, I could have been able to grasp that I was gazing at a face of godlike beauty. I had always assumed beforehand—and, indeed, all my experience since then has confirmed—that when your life is on the line, when you stand on the precipice between life and death, the mind focuses only on keeping you alive. Your eye takes in every detail of the terrain, every clue to where your enemy lies, but nothing of the harmony of the shape of the landscape. Color may be a sign of danger but never moves the heart. Yet, at this instant of vengeance I was nearly unnerved by the splendor that I saw.

Roadblock — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

Guy threw his rifle onto the bunk below and began unbuttoning his shirt.

Alon froze in the middle of pulling his pants up. Guy stopped unbuttoning and stared at his friend.

“I switched with Rafi,” he whispered, so as not to wake sleeping men. He pointed his chin at the reservist lacing boots on the next bottom bunk across the fusty barracks room and over one. His head then signaled to the left, at another man who was already down to his underwear and holding a towel. “Did the ten o’clock shift with Uriel instead.”

Alon was wordless for a moment and then, almost inaudible, said: “Shit, Guy.”

Misgav’s Eulogy for Niot, Six Years / הספדה של משגב לנאות אחרי 6 שנים

גרסת המקור בעברית למטה

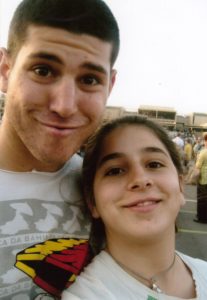

Nioti, can you believe it, six years have passed, six years and I’m already older than you.

Nioti, can you believe it, six years have passed, six years and I’m already older than you.

Six years and I am trying to understand how it makes sense that you disappeared.

Before we had a chance to really get to know each other, before we managed to put all our silliness aside and rally talk about life and to stop being kids. Simply to love.

You left me in the middle of life, just when I needed you the most. We were going to be in the army together, to trade stories about our treks, to talk about the next trip, maybe even travel together, to talk about our studies and way of life, to go crazy at Asor’s and Mizmor’s weddings. Because you and are are two crazy people.

Six years that your death is a lump in my throat. I didn’t know what it meant for me, what I feel, how I express it.

Ilana’s Eulogy for Niot, Six Years / הספדה של אילנה לנאות אחרי 6 שנים

גרסת המקור בעברית למטה

We stand here on a clear spring day, the sixth spring since you fell, as everything blooms. The buds are coming out on the citrus trees in our garden. Every year, when the fruit ripened, I would ask you to go down and pick clementines and oranges. You could reach fruit that was out of my grasp.

We stand here on a clear spring day, the sixth spring since you fell, as everything blooms. The buds are coming out on the citrus trees in our garden. Every year, when the fruit ripened, I would ask you to go down and pick clementines and oranges. You could reach fruit that was out of my grasp.

It is hard to accept that you are not here with us. In recent years we have represented you at the weddings of your friends. At every wedding we see the circles of friendship whose moving force is actually you. And I imagine how different life would look if you were still here with your big smile, good heart, and your special ability to accept life in an uncomplicated and direct way.

Memories: You came to me in the kitchen, pondering out loud. A girl had captured your heart and you were wondering what to do. Your eyes were sparkling and good. I said to you: Tell her what you feel. And you were so happy and you surrounded me with so much love.

And I remember your strong back when you sat in the dining room with the computer during the time you were at home on medical leave, and I didn’t know that those were my last days with you.

Third Day of Spring — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

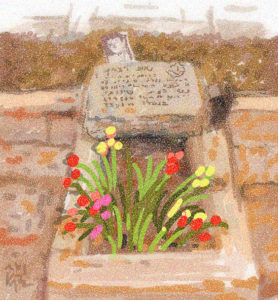

The third day of spring is warm in the sun but cold in the shade. Ilana and I take the day off to head south and see lupines and anemones blanket green hills. But first we have a stop to make. We drive to the Botanical Gardens at Givat Ram for lunch at the café, and then buy flowers to plant at Niot’s grave.

On Niot’s plot, the flowers Ilana planted last year are blooming again, but the stems have grown long and tangled and tough. We try to put at least some of them in order, but realize that they have gone feral and will no longer bow to our will. Not to mention, there were some other brightly colored flowers there, which might have been poisonous flowers, so we dig them all up to replace them with young, soft newcomers, bearing petals of many colors. The sun is warm and I take off my sweater.

We do not speak much. We do not need to; lovers of many years know each other’s minds, and for the last six years we have been tied fast to each other not only by love but also by grief, and intense longing that often knows no words.

Necessary Stories — My New Book!

I’m happy to announce the publication of a collection of twenty-four of the best from the “Necessary Stories” column I’ve written in The Jerusalem Report for the last nine years. Plus one never-before published tale! Information about the book, buying options, and links to related material can be found on the Necessary Stories: The Book! … Read more

Who Walks In? Thoughts on Pesach in Memory of Niot Watzman z”l

From the Tzav-Pesach 2017 issue of Shabbat Shalom, the weekly Torah portion sheet published by Oz Veshalom. The Hebrew version can be foundon the Oz Veshalom website

Haim Watzman

Each Seder night, at the beginning of the Maggid, the telling of the story of the Exodus, we declare “Ha lahma anya,” “This is the bread of affliction that our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt.” We then make another declaration: “Kol dikhfin,” “Let all come eat, all who are needy come and partake of our Pesach offering.” The first mention of matzah is followed immediately by an invitation to anyone who may be passing by to join us, not just for the holiday meal but also to participate in fulfilling the commandment of telling the story of the Exodus and eating the Pesach sacrifice. The “all” of “kol dikhfin” are at poor people who do not have the means to conduct a Seder themselves. (While most English translations render “Let all who are hungry come eat,” the “who are hungry” is an interpretive gloss not present in the Aramaic.)

Each Seder night, at the beginning of the Maggid, the telling of the story of the Exodus, we declare “Ha lahma anya,” “This is the bread of affliction that our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt.” We then make another declaration: “Kol dikhfin,” “Let all come eat, all who are needy come and partake of our Pesach offering.” The first mention of matzah is followed immediately by an invitation to anyone who may be passing by to join us, not just for the holiday meal but also to participate in fulfilling the commandment of telling the story of the Exodus and eating the Pesach sacrifice. The “all” of “kol dikhfin” are at poor people who do not have the means to conduct a Seder themselves. (While most English translations render “Let all who are hungry come eat,” the “who are hungry” is an interpretive gloss not present in the Aramaic.)

A question immediately arises: why do we make this declaration on Pesach, as part of the ritual? After all, on every holiday, indeed every day, we are subject to the commandments of charity and hospitality.

This invitation to the hungry to sit down at our Seder table caused a measure of discomfort among commentators on the Haggadah. According to the laws of the Pesach sacrifice, a person cannot simply be asked to partake of a particular Paschal lamb. The Torah commands: “But if the household is too small for a lamb, let him share one with a neighbor who dwells nearby, in proportion to the number of persons: you shall contribute for the lamb according to what each household will eat” (Exodus 12:4, New JPS). The Sages learned from this verse that the Pesach sacrifice “is not eaten except by those subscribed to it” (Mishnah Zevahim 5:8). A person needs to have been included in a company of people who have subscribed to the same lamb before it is sacrificed; if he has not, he many not eat its meat at the Seder in fulfillment of the laws of Pesach. If that is the case, how can a person be brought into our Seder at the last minute, after the sacrifice has been made and we are sitting and reading the Haggadah?