Haim Watzman

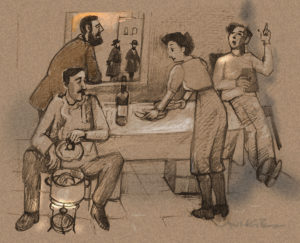

“It is a heavenly chicken,” he pronounced. “There is no pleasure on this earth greater than inhaling the scent of a cooking chicken.”

“How about an orgasm?” suggested Yanai, tipped back against a corner with his legs stretched out, dressed in a white shirt and paint-splattered work pants. The corner went dim as the final ray of the setting sun abandoned the window of Devorah Hannah’s room in Jerusalem’s Fruits of Labor neighborhood. Behind the aroma of the cooking chicken was a dank scent of mildew, brought on an hour before by a cloudburst that had come two weeks too early on that Yom Kippur eve of 1911.

“All great orgasms are, ultimately, alike,” Zealot considered, preening his moustache, “but each excellent repast is excellent in its own way.”

“Zealot has never had either,” Devorah Hannah informed Eliezer, as she set her table for four. The table was the board that served as her bed, with an additional crate added to each leg, with a white cotton sheet serving as a tablecloth. A bottle of Rishon Letzion was already open and waiting. Eliezer gazed out the window at men in black frock coats and black hats striding toward synagogues. He wore the brown gabardine suit that he generally put on only for his meetings with Ottoman officials or Baron Rothschild’s men.

“I can’t read any more,” Yanai sighed, putting down his copy of Brenner’s new novel, On This Side and That.

“Too dark?” Eliezer asked.

“The darkness of the soul,” Yanai said, slowly rising, then pushing the rickety chair toward the table. He stretched his lanky frame and yawned. “When do we eat?”

Israeli fiction

Paper Rule — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

As I rant, her face is forbearing but firm. She holds her pile of folded laundry perfectly steady. My tirade is just a fraction of the pre-Shabbat uproar of tantrums, whistling kettle, beeping microwave, high-volume radio, chair-dragging, clinking plates and silverware that fill my big sister’s small apartment. I take a deep breath in the middle of a loud sentence.

Itay, Steph’s five-year-old (number four of six) walks out of the boys’ room and stares at me. I put my hand on the lintel of the bathroom door ‒ to steady my spirit more than to hold up my body. Maybe I should leave before the rules kick in. But where would I go? Back home to Mom would be worse. Back on the road?

“I’m sorry,” I say. “Of course. It’s your place. I get it. It’s a rule.”

Steph smiles, hugs me, then holds me by the shoulders and looks at me like she used to when I’d come home from school with holes in my jeans that Mom hadn’t yet seen.

“Little sis. I love you.”

Itay reaches up between us to see who will respond first. I pick him up and give him a squeeze.

“Can I just have on record that I think, that of all the Shabbat rules you’ve so carefully laid out and explained over the last hour, this is the most ridiculous?”

The Shirt Off His Back — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

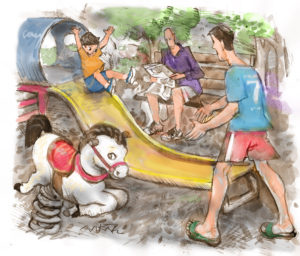

Itzik feels a little hand tugging at his but keeps his eye on the shirt. The hand belongs to Lior, his three-year-old. The shirt belongs to him, to Itzik, but Itzik is not wearing it. A stranger is.

The shirt is purple, long-sleeved, one that Itzik would never have worn on such a hot summer morning. The stranger wearing it has a sculpted, lean face and sits poised, erect but relaxed. Other than the shirt, he has on khaki cargo shorts and New Balances.

“Abba, watch,” Lior pleads, tugging again at Itzik’s hand. Itzik looks down into his son’s bright eyes, which seem to take up most of his face.

“I’m watching, I’m watching!” Lior smiles broadly, but when he sits down on the edge of the slide, his face clouds.

“Go on!”

Lior shakes his head slowly, turning it a full ninety degrees each way.

“Ok, I’ll go catch you.” Itzik clambers down the ladder and goes to the bottom of the S-shaped slide, a tunnel at its top half. Lior lets loose with a child’s primal cry and a few seconds later lands on his bottom on the rubber below. Lior screams, more insulted than hurt. Itzik looks away from the stranger, heaves his son up into a big hug. The stranger looks up at them.

One Flesh — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

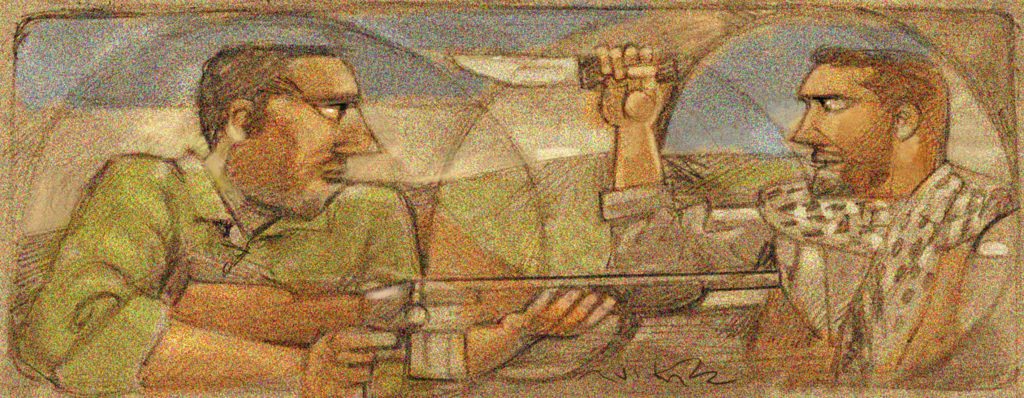

We circle, weapons drawn, two as one, ready to kill.

I raped the boy in April 1948, in a dark corner in the garden of a villa in Talbieh. A few minutes before he had leapt out from between some bushes, a butcher’s knife flashing. Boaz, a pace away from me, had his eye on the balcony above, fearing a sniper, so he never saw the kid who brought the knife down between his shoulder blades, with a shout of Allah akbar!, or perhaps it was something else. The stars were just coming out, but I saw my friend murdered. I saw the blood spurt from his back and chest as he crumpled.

To this day I wonder how, in the heat of battle, I could have been able to grasp that I was gazing at a face of godlike beauty. I had always assumed beforehand—and, indeed, all my experience since then has confirmed—that when your life is on the line, when you stand on the precipice between life and death, the mind focuses only on keeping you alive. Your eye takes in every detail of the terrain, every clue to where your enemy lies, but nothing of the harmony of the shape of the landscape. Color may be a sign of danger but never moves the heart. Yet, at this instant of vengeance I was nearly unnerved by the splendor that I saw.

Roadblock — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

Guy threw his rifle onto the bunk below and began unbuttoning his shirt.

Alon froze in the middle of pulling his pants up. Guy stopped unbuttoning and stared at his friend.

“I switched with Rafi,” he whispered, so as not to wake sleeping men. He pointed his chin at the reservist lacing boots on the next bottom bunk across the fusty barracks room and over one. His head then signaled to the left, at another man who was already down to his underwear and holding a towel. “Did the ten o’clock shift with Uriel instead.”

Alon was wordless for a moment and then, almost inaudible, said: “Shit, Guy.”

The Madonna Lily — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

I make a mental note to consider an essay arguing that Einstein drafted his theory of Special Relativity in these corridors; I notice that as I try to pick up my pace, the carry-on I pull behind me and the laptop on my back gain mass, and the clock on my phone slows down. Yet, according to the signs, I am no closer to Concourse C than when I started out. Then, like Bilbo Baggins catching sight of the Last Homely House, I spy, just off the corridor I am tramping through, an alcove thoughtfully provided by the mad architect who designed this distended monstrosity. The alcove is furnished with a hub of what look like beach chairs set on low pedestals and upholstered in imitation leather. It is silent and empty, and the thought of being able to recline at an angle of less than seventy-five degrees is more salaciously tempting than anything else I have seen this morning. I’m an organized person and my travel philosophy is always get to my gate first, and then rest, but I have so much time that there seems to be no reason not to stop for a brief nap. So I choose a chair that faces away from the corridor, place my carry-on underneath and my backpack for a pillow, and lie down. Out of the corner of my eye, I notice, on the next chair over, the long stem and closed buds of what we call in Hebrew a shoshan tzahor. It makes no impression. I quickly lose consciousness, and when I come to, I scream.

The Treasure Room — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Rachel Eberlein had just languidly stirred honey into her sage tea when she spotted Rabbi Hayyim soaring down from a feathery cloud that hung over Safed and Mt. Meron. It was the only mark in an otherwise clear blue sky. While he was still far too distant for her to make out his face, she knew it was Rabbi Hayyim Vital, her tenant these last two years. Just as people have distinctive walks that make it possible to identify them from far away, so they have their own special ways of flying. Rabbi Hayyim’s path was a series of bumps; he descended a bit, his kaftan billowing and offering a glimpse of his thighs, the then lurched up, then plunged, then lurched up again, all while standing erect with his arms stiff at his sides. It was as if he did not know whether he really wanted to reach earth.

Rachel Eberlein had just languidly stirred honey into her sage tea when she spotted Rabbi Hayyim soaring down from a feathery cloud that hung over Safed and Mt. Meron. It was the only mark in an otherwise clear blue sky. While he was still far too distant for her to make out his face, she knew it was Rabbi Hayyim Vital, her tenant these last two years. Just as people have distinctive walks that make it possible to identify them from far away, so they have their own special ways of flying. Rabbi Hayyim’s path was a series of bumps; he descended a bit, his kaftan billowing and offering a glimpse of his thighs, the then lurched up, then plunged, then lurched up again, all while standing erect with his arms stiff at his sides. It was as if he did not know whether he really wanted to reach earth.

It was a week before Lag B’Omer, and the sun’s rays were still a caress rather than a hammer blow, as in the summer. The magnitude of the day—somehow that phrase from Yom Kippur came to mind, the magnitude of the day—required a woman to sit on her second floor balcony and sip tea (sage tea because her stomach had hurt this morning, even though her time of month had passed a couple days ago). God had decreed it, as evidenced by the fact that her neighbor across the courtyard, Hannah, was also sipping tea on her balcony, surveying the verdant hills that ringed the holy city. She glanced at Rachel and followed her gaze to the sky, and, Hannah was pretty sure, raised her eyebrows.

Rachel frowned. Hannah always had to stick a thorn in her side. Rabbi Hayyim was just a tenant, no more, a way for a poor widow to put bread and cheese and olives on her table. Hannah was the one who should be ashamed of herself. She was remarried now, and should not so closely observe her former husband. She did not appreciate Rabbi Hayyim’s knowledge of the deepest secrets of the Torah that had descended from heaven to the Galilean mystics in recent times, as if God were compensating his people for their exile from Spain. Rachel spoke with him sometimes about the great mission that the Holy One, Blessed be He, had charged his people with, to raise up the divine sparks captured by the shells of evil. At times he spoke quickly, with a fiery intensity; at other times he would say a single word and fall silent and take to his bed for hours. In any case, if the stories were true, Hannah’s leers were out of place. It must have been her fault, she must not have known how to care for a man. Rabbi Hayyim was small and did not eat, and while his face was handsome enough, it had several pock-marks that were clearly visible under his spotty beard. Also, he had no income. In fact, he hadn’t paid his rent for two months, a fact that Rachel reminded him of just as he lunged down from treetop height and crashed loudly beside her, falling on his bottom and crying out in pain.

The Dig at Bab al-Wad — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

At dawn he’d set Klara and Stella to sifting through yesterday’s rubble. An hour later they came to him with an almost pristine Samsung Note 7 with no char marks; others might have tossed it out as just another iPhone. He rewarded them by telling them to take the rest of the day off on the beach, half hoping that he’d manage to slip away there himself to watch them gambol in the waves. Instead, here he was standing on the edge of Pit 3b watching Jawad, the grad student from the co-sponsoring University of Qom, brushing grit off a flat plastic torus. Jawad put his mouth close to the object to blow some dust off and grimaced.

“It’s still dirty,” Yehuda said. He considered leaping agilely into the pit as if he were Jawad’s age, but then figured it was not worth it since Klara and Stella were not watching, and he’d probably fall on his face anyway. They did seem to sit up and notice, though, when Jawad eschewed the ladder and jumped.

“That’s not dirt,” Jawad said, wiping the back of his hand on his beard. “It’s real shit.”

Yehuda fell silent.

“A clincher for your theory?” Jawad held the toilet seat up as if it were a trophy. “This is the Sha’ar Hagai gas station? Identified in that dog-eared family chronicle you lug around as having had the filthiest bathroom between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv?”

Fire — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

Orit races to Yoel’s room as Adam pulls on his pants and tries to think whether there are any essential papers or valuables he should stuff into the pockets of his cargoes. Another tree catches, closer to home; a carpet of flame approaches from the edge of the back lawn, along the wadi. He has a coughing fit as Orit runs back in to the room, two-year-old Yoel swaddled in a wet blanket. She pulls at Adam. Shouldn’t there be screams, shouts, from the neighbors, he wonders as he coughs. Gandhi trails them, looking back at the window, and Yoel chants “Go way fire. Bad fire!”

When they emerge from their front door, Yoel exults: “Firetruck!” They stand on a peninsula, an enclave of houses surrounded on three sides by flames. Five firemen in yellow suits are hosing the trees and gaping at them.

“What the hell!” one exclaims, dropping his grip and running over. “Where have you been? We evacuated the whole street nearly an hour ago!”

Orit hugs Yoel close. “We were sleeping. No one woke us up.” The heat was almost unbearable but Adam could feel the cold of the November ground welling up through the soles of his sandals.

Caught in the Meshwork — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

When Nir woke up in the dark, Heli was crying in her sleep. At the foot of the bed, Ben Ha-Ha, the cat, was crouched in defecating position, and from the balcony, outside the sliding door, a pigeon screamed. As none of these things made sense, Nir assumed he had only dreamed of waking. He turned over to his other side and, back to all the apparitions, descended to another plane of slumber.

When the alarm roused him, some time after dawn, Nir groaned, turned over, and opened his eyes. Heli was out on the balcony, looking up at the meshwork roof of the pergola they had installed just before the holidays. The balcony, which opened from their room, faced west; a last bit of night remained there. Nir groaned again and then propped himself up on his elbow.

“I feel like I didn’t sleep at all,” he grumbled. “I had this horrible …”

“Shit!”

Heli brought him toilet paper and wipes and a rag to cleanse the dirty spot on the floor. She also reminded him that she had told him not to give in to his mother’s insistence that they adopt her cat.

Nir put on t-shirt, rinsed his foot in the shower, and then tiptoed into the boys’ room. Ben Ha-Ha, a miniature panther curled up blackly in the crook of Elisha’s elbow on the lower bunk, opened phosphorescent eyes as Nir began to sing. For two minutes nothing happened, but then Omer, in the upper bunk, suddenly sat up, eyed his father with exasperation, and dove down to bury his head under his pillow. In the pale dawn Nir thought he caught the glimmer of the first faint fuzz on his older son’s upper lip. Could it be? Wasn’t it too early for that?

Peck of Pickled Pollsters — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

I used to try to contain his cascading consonants and viva voce vowels, but then relinquished all resistance. Frankly, I was happy that there had been a hiatus—for some four fortnights my Skype had been silent, but then belatedly on my browser, just as I was autographing my absentee ballot, his avatar aparated.

“Hey, Frank, wherya been?” I queried on my qwerty keyboard.

Post-pregnant pause, Frank formulated: “Brooding on the blight that plagues the planet.”

“As always,” I answered.

“I have been agonizing over William Butler’s legendary lyric: ‘a kind of chaos is unleashed on the universe, the blood-blinded tide is untethered.’”

“You mean Yeats?” I yammered. “But you revise his vocabulary.”

“Dare you doubt my veracity in verse?” Frank was awfully offended.

With a sad sigh I said: “Apologies, amigo. This señor is at your service.”

“I call with concern in connection with your far-off franchise.” My chum chided: “As our buddyhood began before our birth, I have grave grounds for goosebumps. Do you value your vote? Do you take your suffrage seriously?”

“Absolutely,” I affirmed. “In fact, my ballot is before me.”

Besieged — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

Chaya glanced at the boy in the bed. He was lying on his back, staring at the mildew on the ceiling. His sun-fired head and neck looked as if they had been grafted on to his pale body. She quickly pushed her arms into the sleeves of her smock and stood up. The smock did little to warm her and floor was icy. Now the whole door shook and the boy’s friend shouted: “Hey, you two going into overtime?”

“It’s Ari,” the boy said matter-of-factly. He stroked the line of his hairless chest with his left hand and his right moved down under the corner of the blanket that covered his loins.

She brushed her hair, stooping before a tiny mirror propped up on a rough wooden table against the wall. “Should I let him in?”

“It’s not his real name,” the boy said, turning to look at her.

“It usually isn’t,” she said. “Mine isn’t. Nor is yours.”

“You speak Hebrew so precisely. I mean, for someone who’s been here just two years,” the boy said. Then he quickly added: “I like that.”

“Get dressed and don’t forget to pay.”